My New York Trilogy

Take a backwards journey through a Manhattan day full of Austerian coincidence and synchronicity.

Let’s start with the ending, like a mystery writer deciding on the murderer, the weapon, and the location before telling the rest of the story.

I spent about 48 hours in New York recently, my driving goal being to witness Christian Marclay’s installation “The Clock” at MoMA before it closes in a couple of weeks.

But it turned out there were two other events happening Monday which, by the end of the day, I could feel fusing intriguingly together in my imagination as I sipped a Dirty Vesper at Le Dive while waiting for the 9PM Chinatown bus home to Philadelphia.

3. The New York Trilogy

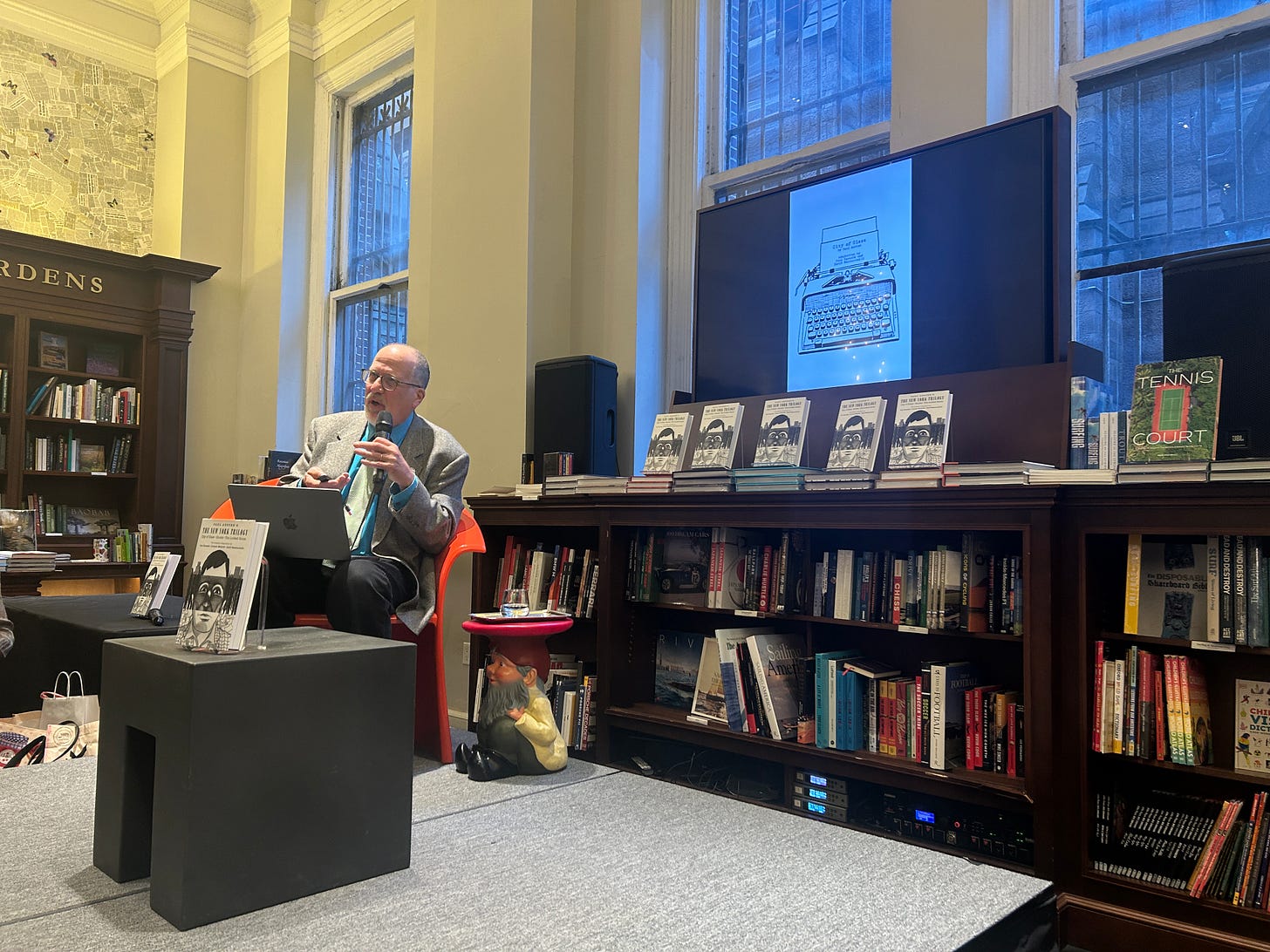

A little after 6PM I rolled my little carry-on suitcase into the elegant Rizzoli Bookstore to watch my friend Paul Karasik talk about his newly completed comic adaptation of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy. If you are not aware, Karasik published a version of City of Glass, the first book in the trilogy, in collaboration with David Mazzucchelli back in the late 90s and I consider it to be an all-time classic of comic art as well as an examplary adaptation from one medium to another.

Karasik has now completed adaptations of the other two novellas in the series, one with Lorenzo Mattotti tackling the art and the other with Karasik taking on both art and adaptation.

Karasik described how he calculated that for every 100 words that Auster had used, he could only use 70 or so to fit the prescribed page limit, but that instead of being a hindrance, this restriction—and here he paused to look me in the eyes and gesture meaningfully toward me for those in the know (like you, my newsletter subscribers!)—was actually a source of strength because it helped whittle down the text to its essentials.1

He spoke about how each novella dealt differently with our relationship to literature and storytelling, both as writers and as readers. All three books deal with lonely, male writers who get lost in their own literary worlds. And if you’ve ever read any Paul Auster books you also know there’s a large amount of metafictional rabbit holes, kafkaesque conspiracy theories, and improbably coincidences in his work…

2. The Shrouds

Earlier that afternoon, I had scrambled across Manhattan on a few slow buses to meet up with my friend Bruce to catch David Cronenberg’s new movie, The Shrouds.

We both appreciated the movie, with its odd blend of grief and slapstick (humor is an underrated strength of Cronenberg’s). I particularly appreciated seeing such a sensuous and occasionally sensual film that focused entirely on older people’s bodies—there’s hardly a character under fifty years old.

As the narrative progresses, conspiracies and paranoia start to take hold of the protagonists and by the end, like poet-detectives in a Paul Auster novella, they start to lose (or relinquish) their ability to distinguish rationality from imagination, reality from dreams.

I walked Bruce to the 6 train and we reflected on the passage of time, our own aging bodies, those of our remaining parents…

1. The Clock

I’m very busy at home these days but I couldn’t risk missing out on The Clock, an installation by Christian Marclay that is viewable only until May 11. So, Monday morning, I found myself on the subway to the Museum of Modern Art.

The concept of The Clock is simple: in a black box theater, a screen shows a looping 24-hour film made up entirely of shots (ranging from a split second to several minutes) of the depiction of time from throughout the history of film:2 close-ups of watches, giant train station clock faces, people telling each other the time, church bells ringing, and so on.

The theater has about 18 small sofas and some standing area and you are welcome to stay as long as you like once you enter. I spent a little over an hour in there and it was a bare minimum for me: I could have easily stayed the rest of the day.

I knew I was going to like The Clock—its conceit is too aligned with my interests in constraints, appropriation, and experimental narrative not to appeal to me—but I was still impressed by how many ways there are to appreciate it.

As you watch the scenes flow by, you are at first overwhelmed by this overdose of visual information. But quickly you start to notice time pieces in all their manifestations: a cowboy consults his pocket watch, a factory worker punches into work, the police chase robbers down a busy London street, in black and white, as a discreet clock hangs over a doorway in the background. I reflexively pulled out my phone a few times: yep, that’s the time all right.3

Then there’s the fun of identifying the films, kind of like picking out samples in a hip hop production: That’s Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson! There’s Zazie in the Metro! Is that a Satyajit Ray film? It’s just a character running down a train platform but I’m almost sure that’s from Kieslowski’s Blind Chance!

At the same time, you start to notice certain narrative similarities between all of these scenes and they begin to form a kind of abstract story, seesawing from bank robbers and conspiracy theorists racing against the clock(s) to bored and listless loners waiting around for someone who’s probably not going to show up.

Then there are scenes where characters talk about time or clocks: in one extended scene, a young man describes a clock that, once set, will run perfectly for a hundred years and then throws a tantrum (smashing a grandfather clock in the process) when his mentor questions the point of such a folly… I was pleased and not at all surprised to encounter Harry Lime giving his famously cynical speech in The Third Man about the culmination of Swiss culture, “the cuckoo clock!”

What surprised me perhaps the most was how carefully and seamlessly all of these disparate shots were edited together: there were few jump cuts, rather, if someone opened a door, the next scene would show a character in another film standing at the threshold. In one awful scene, we see a boy get run over by a car somewhere in Europe in the 1950s, and then we cut to a man looking sadly downward out a window—a perfect match cut, but he’s in black and white and in a different era.

I couldn’t stay as long as I would have liked because I had plans to meet a friend to see a movie later that afternoon. I kept thinking I should check my watch and leave on time only to catch myself: I’m sitting here watching time pass by the minute on the screen in front of me!

When I decided it was time to go, I gave up my sofa corner spot and stood up, unfolding my jacket. As I reached the exit I took one last look over my shoulder. If you are at all familiar with my book 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style, you’ll understand why this random scene from a movie called The Assignment was the exact, perfect instant for me to leave the exhibit:

Paul Auster couldn’t have written it better.

As I left the museum, heading for the subway, the city hummed with time and movement, the midday light vivid like Technicolor film stock. I couldn’t help but scan for clocks or watches on passersby in my peripheral vision.

But I couldn’t linger: it was past 1:15 and I had an appointment I couldn’t miss at 2PM…

Another constraint imposed by Paul Auster was that although Karasik was allowed to make cuts, any text that appeared in the book had to be Auster’s exact words.

and some TV—I spotted Stringer Bell checking a very expensive watch at around 12:30PM

“The Clock” runs for 24 hours and is synchronized to the local time—there’s a little bit of wiggle room there, but you’re rarely more than 30 seconds away from the actual time.

Oh man, I *love* Karasik's version of The City of Glass. (I even wrote an essay about it: https://stephenfrug.blogspot.com/2007/03/100-great-pages-paul-austers-city-of.html) I am really excited to hear he's doing the other two!

I have wanted to see The Clock since I heard about it, but I haven't had the chance, yet, alas. I wonder how long it's playing for?

(Just to complete the trilogy: The Shrouds I haven't heard of before, but you sell it well! I'll keep an eye out for it.)

I sat through about 45 minutes of "The Clock" back in 2016, when it first came to NYC. I, too, was struck by how the clips initially seemed random but eventually resolved into a kind of comprehensible narrative. I'm not sure if it was intentional or if it was just the human desire to impose linearity on chaos, but it was striking.

If you've never read it, this old New Yorker piece about the making of the film is absolutely fascinating:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/03/12/the-hours-daniel-zalewski