Thinking inside the Box

Or, the Method to My Madden-ness

Welcome back to the Labyrinth of Constraints!

With my comics collection Six Treasures of the Spiral coming out soon, this seems like a good time to share a (slightly adapted) version of a text I wrote to introduce the back matter of the book, which features notes, diagrams, and insights into the many constraints I have used to make comics over the years.

You’ll read the story of how I became fascinated with formalism, constraints, and the French literary group Oulipo and I’ll explain why I find it so rewarding to work in this offbeat way.

But first

I’m excited to announce that Six Treasures of the Spiral: Comics Formed under Pressure will have an exclusive pre-release1 debut at SPX, the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, MD on September 14-15. I’ll be tabling with Uncivilized Books (tables W 47-48) and I’d be happy to sign a book or two for you.

I’ll also be offering a free tritina comic workshop on Saturday from 5 to 6:30PM: you can sign up for it here.

Behind the Method to My Madden-ness

For the last 25 years or so I have processed almost all of my artistic activity (whether as cartoonist, artist, musician, or budding poet) through the lens of what I often refer to here on my Substack as “constraints.” Where did I pick up that term and what exactly do I mean by it?

After college, in the early ‘90s, when I was just starting to make comics, I was working at a bookstore2 in Ann Arbor, Michigan and one day a coworker handed me a copy of a book called Exercices de style from the French language section of the store. It was a series of short texts which all told the same story but in a different style each time: backwards, using only interjections, as a sonnet, as a blurb, in phonetic English… I was hooked and what’s more, I knew right away that I wanted to take this idea and use it to make a comic. I honed my craft for a few years before embarking on the project which was eventually published as 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style. As I worked on that book—which involved drawing the same one-page comic 99 times, using different points of view, different drawing styles, and so on, I had a lot of time to get curious about the author of the book that inspired me, Raymond Queneau.

Discovering Oulipo

I learned that Queneau had at one point enlisted his friend François Le Lionnais’s help to work out the math behind another playful yet fiendishly difficult experiment of his, Cent mille milliards de poèmes or One Hundred Million Million Poems. That project consisted of ten sonnets with each line printed on a separate strip of card stock so that you could recombine any of the lines of any of the sonnets in the manner of those children’s flip books where you can combine the head of a lion, the body of a snake, and the legs of a horse. (Those books were, in fact, his initial inspiration.)

The two men figured out that when the chimera-flip-book format was applied to ten 14-line sonnets, it would generate 10-to-the-14th-power poems—that’s a one with 14 zeros after it! It would take multiple lifetimes to read every poem.

These discussions the friends had about the intersections of mathematics and experimental poetry excited them so much that they created the Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop3 for Potential Literature) or Oulipo, in 1960, and ever since then, the group has met once a month to have dinner, drink red wine, and discuss mathematical and other types of structures that can be adapted as rules for writing poetry or prose.

Creative Innovation through Constraint

The term Oulipo most often uses for their creative challenges is “contrainte” or “constraint.” While this word has many negative connotations (deadlines, financial limitations, lack of resources, and so on), Oulipo insists on the creative and even inspirational power of submitting yourself willingly to a limitation—and the more bizarre and challenging, the better the potential results. They have invented constraints like the snowball, a text that begins with a one-letter word, then two, three, four, and so on. They have also identified forgotten or underappreciated constraints in literature, from fixed poetry forms like the pantoum and the sestina to eccentric writing challenges like the lipogram, a text written without the use of one or more letters, famously associated with oulipian Georges Perec’s e-less novel La disparition, translated/adapted by Gilbert Adair as A Void.

When I discovered Queneau and Oulipo, I was immediately hooked by this idea of provoking inspiration through these kinds of challenges. Up until that point I hadn’t found an approach to creating comics that jibed with me: I knew I didn’t want to tell straightforward, character-based narrative stories. But I also didn’t want to do autobio, humor, or weird-for-weird’s-sake comics—or rather, I wanted to do a bit of all of that stuff but I lacked a framework that would give cohesion to my work. As I learned more about the work of Oulipo I recognized tendencies in my own work to use repetition and formal conceits (like my one-pager “House Music” from 1994, created before I learned about constraints). I also saw parallels in other art that I liked, from the morphing Sunday pages of Winsor McCay to the schematic diagrams Brian Eno included on the album covers of some of his ambient music.

I read what I could about Oulipo—this was the mid 90s, when the internet was still in its infancy (Wikipedia didn’t go online until January 2001)—and started taking note of constraints that I wanted to adapt into comics. I was helped enormously by The Oulipo Compendium, edited by Alastair Brotchie and the Oulipo member Harry Mathews, one of the few resources available in the US at that time, along with David Bellos’ biography of Georges Perec. I also picked the brains of writer and poet friends as well as like-minded cartoonists, particularly Tom Hart, Jason Little, and Tom Motley.

I incorporated a few of these discoveries into my own “exercises in style” project—a palindrome and two anagrams being obvious nods to the word games celebrated by the group—and I became increasingly eager to wrap that project up so I could continue my explorations of Oulipian constraints in comics form.

Enter Oubapo

Then, serendipity, if not synchronicity: I was at the comic book store Million Year Picnic in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in around 1999 when Tom Devlin (who was working there while also publishing my second book, Odds Off, with his Highwater Books) placed in my hands a French comic called OuPus 1, published by the esteemed independent comics publishing collective, L’Association. My jaw dropped as I registered the acronym Oubapo, spelled out as Ouvroir de Bande Dessinée4 Potentielle—Workshop for Potential Comics!—along the spine.

It turned out that in 1992 (around the time a friend at the bookstore I was working at had shown me a copy of Queneau’s Exercices de style) some of my favorite French cartoonists—Jean-Christophe Menu, Lewis Trondheim, Killoffer, among others—along with the comics semiotician Thierry Groensteen, had started a comics offshoot of Oulipo dedicated to exploring the intersection of comics and constraints—precisely what I had been absorbed by for the last several years!

I had clearly found my tribe, one which shared an approach to creativity that brought into focus a whole host of previously vague ambitions and ideas I had about how I wanted to go about making comics and being an artist.

The Joy and Challenge of Constraints

If you’ve done any writing yourself, whether it be comics, fiction, poetry, or music, you are probably familiar with the idea of a prompt. A prompt is a keyword or theme that gives you a starting point for creation; something that gets you past that dread of the formless blank page. Prompts are doubtless useful, but I have always felt uncompelled by the notion of making a comic on the subject of, say, thunder, with no further guidance. A prompt gets you started but then you are on your own. What appealed to me from the start about constraints is that, unlike prompts, they accompany you—and even sometimes haunt and pursue you—throughout the course of a creative project.

But why is it appealing to have a rule hanging over your head, forcing you to constantly check your work, twist your drawings and words into some predetermined framework?

Here’s what’s slightly magical about constraints

When you give yourself a weird rule to follow, the anxieties you probably associate with embarking on a creative project from scratch—What do I say? How do I start? Do I have what it takes?—fall by the wayside. Instead, you find yourself switching to problem-solving mode. You dramatically wipe the art supplies off your desk and unfurl your war map. You pull out the thumb tacks and red yarn and attack your bulletin board…

As you grapple with a constraint, at least two things happen: one is that your usual self-doubt and hand-wringing will diminish and even vanish, just as did your fear of the blank page. You are suddenly too busy navigating an obstacle course to be distracted by such trifles.

Deep play with “ill-structured problems”

Another thing that happens when wrestling with constraints is that you enter a state of profound concentration, what the writer Diane Ackerman calls “deep play.” It is similar to the focused-yet-zoned-out feeling you get when you are halfway into a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle. With the significant difference that when you come out the other end of the project, the result is not a predetermined image but a brand new work of art that will often surprise you.

In her book, Creativity from Constraints, Patricia D. Stokes posits that structures like jigsaw or sudoku puzzles are “well-structured problems” with satisfying but unique and predictable solutions. Whereas constraints in the way Oulipo and I use them create what she calls “ill-structured problems” that force one to look for novel and unrepeatable solutions. I believe that I could employ any one of the constraints I have used countless times and come up with countless different works. That’s part of the enduring appeal for me of working this way.

All of this is not to argue that using constraints is a quick-fix or miracle formula for making great art. It’s a long, circuitous route with no guarantees of success. I have certainly hit a few dead ends and lost my way in a few labyrinthine side quests on this journey. Nonetheless, I am deeply appreciative of the guiding constraint hovering over my shoulder that continuously brings my awareness to my own creative process, helps me avoid clichés, and pushes me ever deeper into new and exciting territories.

Give it a Try: Oulipo and the Spirit of Sharing

Here on this Substack, I’ll be sharing constraints I’ve used for many of my comics—including, of course a large number from Six Treasures of the Spiral: Comics Formed under Pressure (and I’ll take this opportunity to remind you that you can now pre-order it from the publisher).

One thing I admire about Oulipo as a group is that their work is intended for sharing—these are not proprietary constraints, you do not need to ask permission to make a palindrome or a lipogram.

There’s nothing like trying out a few constraints yourself to get a sense of how much they can turbocharge your creativity and inventiveness. Plus, they are really fun to share. Feel free to have a go at any of the constraints I you find in my book or here on my Substack—alter them, recombine them, jettison them halfway through: they are for everyone to use as they see fit.

A Special Note for Teachers

In addition to this Substack and the back matter in my book, I have set up a landing page5 on my website that has a bunch of resources you can use for teaching (comics or pretty much anything else) using constraints featured in this collection and many others. I hope you’ll keep my informed about your activities, I love to see new examples of constrained comics and art.

As always, I’d love to see your work if you make one of these (or something similar). And remember that with a paid subscription you can share it with me in my Chat or in one of my periodic group Zooms.

Three Things I've Been Enjoying

1

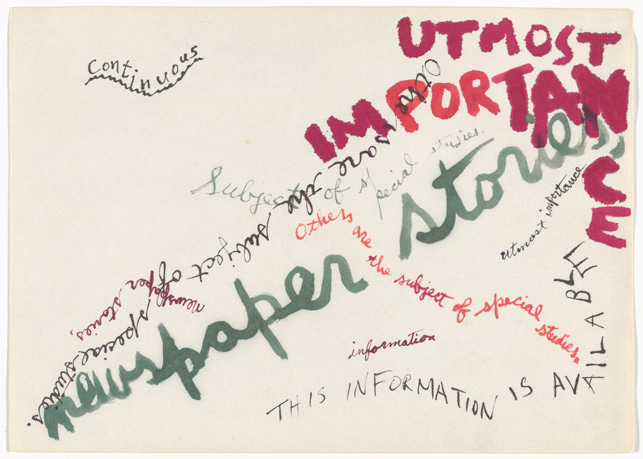

“Asymmetries” by Jackson Mac Low

I have a long list of artists, poets, musicians, and cartoonists to check out and I’m perpetually years behind on it. At some point a few people pointed me towards the graphic work of the poet Jackson Mac Low (1922-2004). I think this must have been in relation to my 20 Lines drawing series because I can see some visual kinship there. His work with words and calligraphy is also inspiring.

Although the final execution of these drawings is quite organic and intuitive, they are derived from rigorous chance-based acrostic procedures he called “asymmetries,” inspired by his friend and mentor, John Cage.

I’ve been looking for a new drawing project and Mac Low’s challenging work encourages me to continue thinking about lines, words, ink, and process.

2

The Raincoats + Jenn Pelly’s 33 1/3 Book about their first album, The Raincoats

I found Jenn Pelly’s book about The Raincoats and the making of their eponymous first album in the spinner rack of my local used bookstore, Lot 49 Books. The band is not on my regular rotation these days but they were part of the pivotal soundtrack of my early adulthood alongside other creative and innovative bands clustered around Rough Trade Records around 1979-82 or so.

Listening with fresh ears, I’m falling in love all over again with this amazing band. Their fearless and confident amateurism is worn as a badge of honor. They were punk in the sense that has always meant the most to me: non-conformist, unconcerned with trends (while having great style!), collaborative, exploratory…

I came across this wonderful live performance of one of my favorite songs of there’s, “Only Loved at Night” from their second album, Odyshape:

3

The Zabîme Sisters (Les sœurs Zabîme) (1996) by Aristophane, translated by Matt Madden

Speaking of oldies but goodies, I was talking to a friend about my translation work and it’s always worth extolling the virtues of this beautiful, funny, observant, and deceptively simply book.

Notice Aristophane’s impressionistic dry brush, the wonderfully expressive body language (look at the boy desparately craning his neck in the third panel), but also his often unexpected, “candid” framing:

We simply follow the adventures of three sisters and the schoolmates they run into over the course of an ordinary summer afternoon on the cusp of young adulthood but Aristophane Boulon, who grew up in Guadeloupe and moved to France to study art, suffuses the book with nostalgia combined with a clear-eyed, ironic distance, gently mocking the foibles of these beautiful young people.

Shout out to Nic Breutzman for the excellent lettering job!

Thanks for reading. I hope you’ll share this post if you enjoyed it and feel free to comment about my essay or any of my “Three Things.” See you soon.

The official release date is October 28 but you can pre-order now from Uncivilized Books and receive a TBD piece of art with your book.

Borders Book Shop, Store #01!

The word ouvroir actually has a very domestic and feminine connotation, meaning something like “a place where a group of women or nuns assemble to do needlework.”

Most of you probably know that bande dessinée (“drawn strip”) is the French term for comics.

very much a work in progress. I welcome comments and requests!

I completely forgot about « Exercices de style » but it is the same exact book that got me into this constraint thing when I was in college (around 2014, I was then 15 years old). I haven’t really done any constraint comics, but I discover Lewis Trondheim, Menu etc and I instantly found all this thrilling. Maybe I should give constraint comics a try, as I am now making amateur comics on my own again. Thank you for sharing your story, it was a good read.