Three Is a Magic Number: The Powerful Simplicity of the Tritina

a constraint borrowed from poetry that is a dynamic creative generator

This is my first newsletter on Substack and it’s part of a series where I highlight creative constraints or challenges that I have used in my comics and teaching. I’m eager to dive right in but stick around until the end and you’ll find some news and three recommendations.

So, what’s a tritina?

I

I'd like to introduce you to a simple yet challenging fixed-form poem that you can adapt in any number of ways to create comics, stories, poems… or Substack newsletters. The tritina was created by poet and teacher Marie Ponsot. It has its roots in the more complicated sestina, a famously challenging medieval French form which I will surely delve into in a later newsletter—I'll just say for now that it is made up of six six-line stanzas and each stanza must feature the same six end words (or repetons) in a different, predetermined order. Ponsot is more of a miniaturist so she stripped the constraint down to three stanzas and three repetons, followed by a one-line "envoi"1 that must use all three words. It's simpler, yes, but that doesn't make it easy: you still need to find three words that will work in multiple contexts. You need to pick words that are not too obvious, like "love" or "rose" while avoiding overly incongruous words like, say, "orange" that risk running the whole thing into the ground.

II

But say you do choose to use "orange": well, the tritina is based on repetition instead of rhyme, so on that count at least, you're in the clear! Let's take a look at what Ponsot did with the form:2

LIVING ROOM The window’s old & paint-stuck in its frame. If we force it open the glass may break. Broken windows cut, and let in the cold to sharpen house-warm air with outside cold that aches to buckle every saving frame & let the wind drive ice in through the break till chair cupboard walls storm hit all goods break. The family picture, wrecked, soaked in cold, would slip wet & dangling out of its frame. Framed, it’s a wind-break. It averts the worst cold.

Let's take a look at how she has used the three repetons: frame, break, and cold:

I love the image of an old picture frame barely protecting the memory of a family perhaps long dead. Whereas "frame" is an unexpected word, Ponsot has used the constraint of repetition to almost hammer us with the march of time with "cold" and "break." The photo, the window, the living room, the house, the family: they are all so fragile, liable to break and let in the cold, cold, elements at any moment.

III

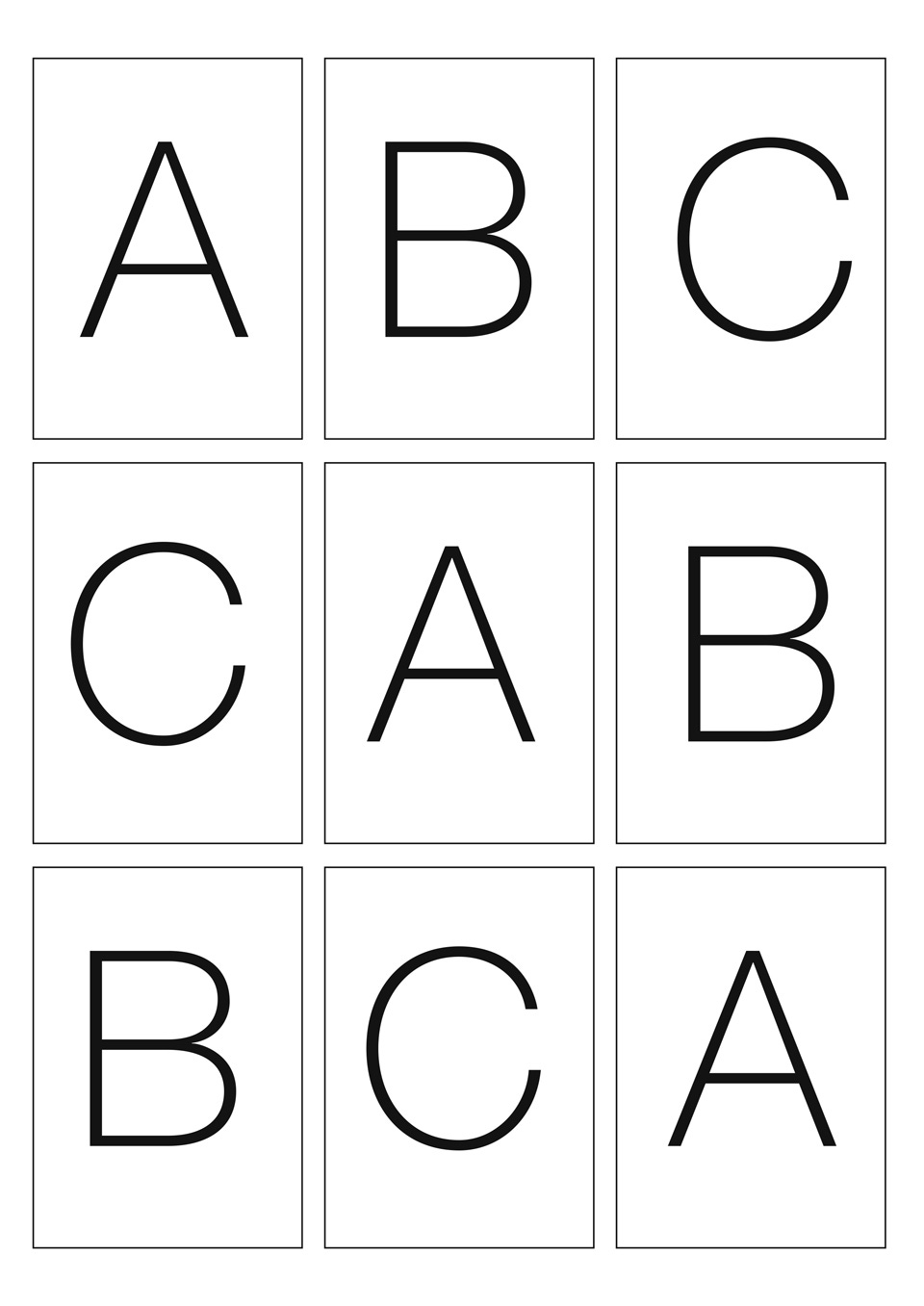

An important feature of this constraint is that the three repetons must repeat in the same order each time:

123

312

231

The envoi, or send-off, repeats the initial order but in a single line. I love a good diagram, and the poet and mathematician Marian Christie, in an excellent blog post on this form, visualizes the algorithm governing the changing order of repetons as a sequence of rotating equilateral triangles:

If you omit the envoi you can call this form a terina (terine in French), an example of which you can find on the Oulipo website in the orange-coded section devoted to a vast list of constraints (mostly in French). Raymond Queneau made a list of all the possible variations on the sestina (collectively known as n-ines or quenines, in his honor) and the three-repeton version is exactly this: a tritina without the envoi.

Envoi

In my own teaching, I have discovered that the tritina can be adapted fruitfully to comics and other media. I'll move along to some examples below but I want to end this introduction by pointing out that I used the constraint myself in order to help my composition. Two of the three repetons are a bit harder to spot since one is the subject of this post and the second is the subject of this Substack (hint: it's not "repeton" though that is ironically the most-repeated word in the whole newsletter!). The third one is easier to spot but I'll spell it out in case you're curious: orange.

Make a Tritina in the Safety of Your own Home

What's cool about adapting the tritina (or terina) for comics (or drawing, or collage, or any other 2-D medium) is that you can map it to a nine-panel grid—a pretty classic one-page comics format. I use this a lot in various workshops and class visits and I always share some version of this diagram:

You can take this grid as a starting point and plug in pretty much any value you want for A, B, and C. You could certainly use three words but I encourage people to explore visual and narrative possibilities: the repetons could be colors, characters, word balloons, points of view… What’s more, each repeton can stay the same in each panel (A might be an apple, for example) or you could come up with variations (A might represent an apple in panel one, a glass of cider in panel 5, New York City in panel 9).

You might notice that I have not included an envoi in my comics grid so it’s technically a terina. This is partly an early oversight that I haven't gotten around to updating but it's worth pointing out that the form also works just fine without the envoi—additionally, it’s more expedient in a classroom situation. When I teach it now I like to offer the envoi as a kind of bonus constraint that people can work into the title or into a wide “mini panel” at the bottom of the page such as you might find in newspaper comics like George Herriman's Krazy Kat or Tony Millionaire's Maakies.

Terina or Tritina, they both are a fun challenge that can produce exciting results. Here are two examples from workshops I’ve taught:

Punch's Terina, by Jason Robinson (2017)

Jason Robinson actually gave himself two sets of repetons for this page, can you identify them? There are three words—line, curtain, and light—and there are also three colors—red, green, and blue—which all cycle through the three sequences to make this funny, in-your-face character sketch.

Notice in particular how the keywords are sometimes represented visually (a curtain, the cheeky lines of cocaine in the first panel) and sometimes appear as text but with different shades of meeting (see the other two occurrences of “line”).

Sixty Second Troilus & Criseyde by Kirsten Haas Curtis (2023)

This one’s going to have you digging up your old Norton Anthology of English Literature: it’s a summary of Geoffrey Chaucer’s epic poem (not the Shakespeare play, hence the different spelling) in one page. The repetons are the three main characters: the two lovers and Criseyde’s sly uncle, Pandarus.

But there’s a lot going on, for instance notice how Troilus seems to fall in love—and into bed—with Criseyde in his own little animated drama when you read his panels diagonally! I don’t know if Kristen planned that out but she can certainly claim it as her own: these are the kinds of storytelling surprises that can result from a diligent (and playful) engagement with constraints.

Notice, too, that this is a proper tritina comic: it features a final “envoi panel” where all three repetons (characters) interact one last time, summing up the comic.

So, Let’s Give This a Try!

I’d like to invite you all to try a tritina (or terina) in whatever medium you like and share it here with me (or on your platform of preference) along with any thoughts you’d like to share about what the process was like for you.

I’m finding my way on Substack and am trying out its different features so you can Comment here or tag me in a Note.

I’m on social media less and less but I do still drop into my Instragram with some regularity.

For my paid subscribers, this will kick off my first regular Zoom workshop so now would be a great time to join the club if you’ve been thinking about it!

One more example: a terina by yours truly

I recently tried my hand at a few terinas and it was a lot of fun. Here’s one where I started with a little schematic using a circle, a square, and a triangle as repetons instead of words. Then I composed the poem by looking for words associated with those three shapes:

In the cold glow of a full moon, I spotted it outside my window. It looked like a backyard teepee But I knew it was a pyramid, Its entrance controlled by a stone wheel Accessible by a hidden panel. Inside there was a room containing a box Marked with a yellow warning sign: I knew I would never again see the sun.

When I shared this with my writing group (shout-out to the Fun & Games crew from Lot 49 Books!) I wondered aloud if I should include the diagram as part of the poem and it sparked a really interesting conversation about the value of “showing your work.” In the end, everyone was in favor of including the diagram since it both acts as an intriguing illustration as well as a key to understanding how the poem was constructed—without necessarily taking away from the mystery of the final text, which surprised and even spooked me a little.

Some news:

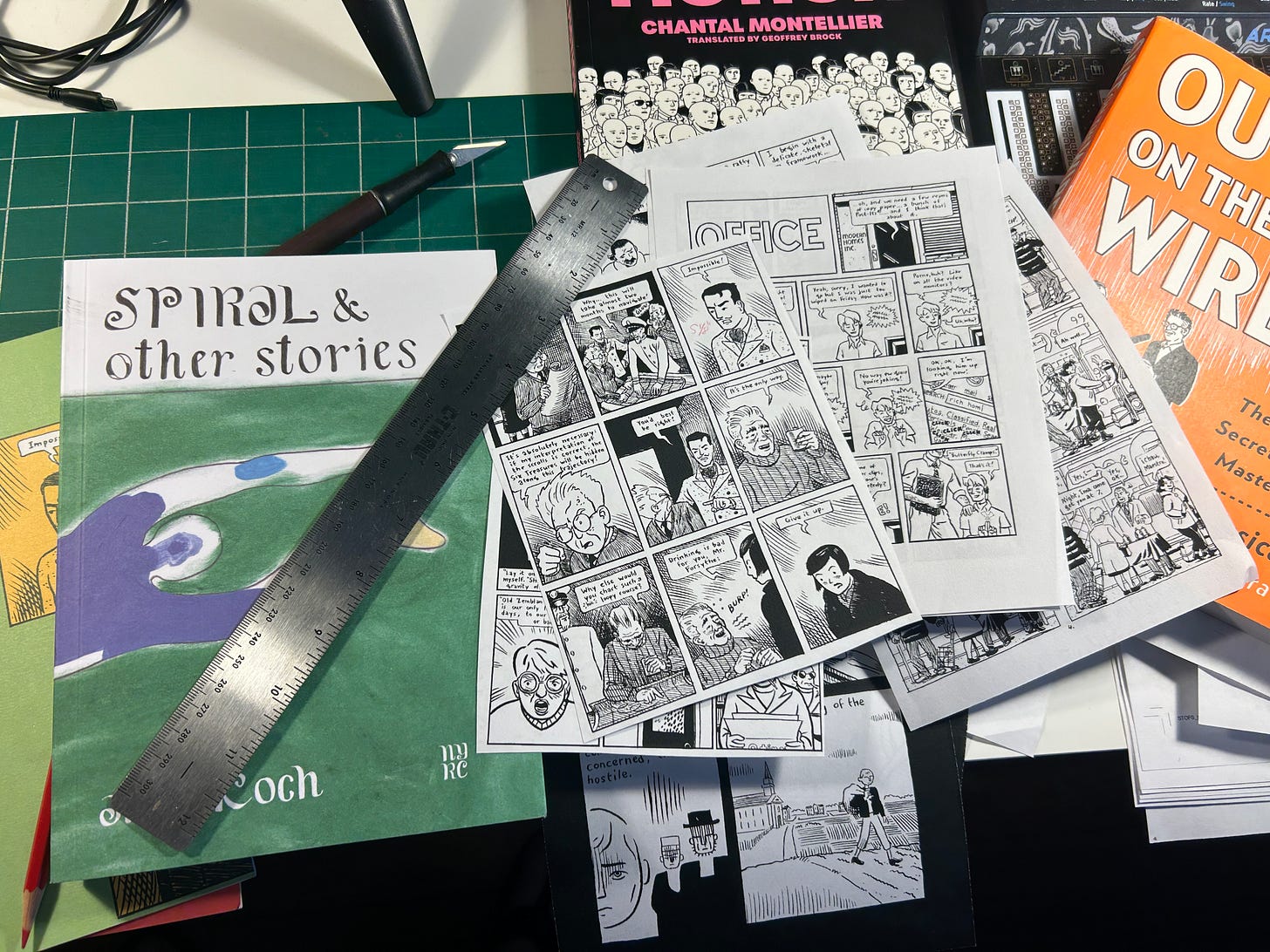

Very quickly, since we’re running long, here: I am busy at work putting the finishing touches on my new book, a collection of my best short comics made with constraints from the last 25 years. I’ve been shuffling the story order, writing a long afterword about my process using constraints (parts of which will be excerpted—and expanded upon—here soon), and tweaking the trim (or final book) size:

The book is called Six Treasures of the Spiral: Comics Formed Under Pressure and it will be published by Uncivilized Books this fall.

Three things I've been enjoying

1

Jack Bruce’s early solo albums, Songs for a Tailor and Harmony Row, recorded after the break-up of Cream and which I have stupidly ignored for all these years, are an inventive blend of jazz and folk rock with haunting melodies and hardly a guitar solo in sight except for Chris Spedding’s proto-No Wave slide guitar at the end of “To Isengard.”

2

Not All Propaganda Is Art, Benjamen Walker’s fascinating, novelistic account of the CIA’s engagement with the literary world during the Cold War. It’s kind of like a season of Serial produced by Thomas Pynchon.

3

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo, my second time reading this deeply affecting, hallucinatory reading experience, a huge influence on the “magic realism” generation of South American authors, of course, but to me it also shares some DNA with Samuel Beckett's novels and even the French nouveau roman in its panoramic, tableau vivant portrait of a place and time.

Edit: I initially posted this with the less pretentious, English spelling, “envoy,” however now that I’m copyediting my new book I consulted a bunch of source and style does seem to be the French word “envoi,” with or without italics.

“Living Room” appears in the collection Springing: New and Collected Poems (Knopf, 2002) and I discovered it in an article called “Marie Ponsot: Wandering Still” by Julie Larios in Numéro Cinq Magazine, Vol V, No. 1

test comment

Awwww thank you for including my comic and for your lovely and insightful reading of it! What a wonderful surprise!